The UHD60, as mentioned, uses a different color wheel than the UHD65. Theoretically, that’s why you pay $500 more for the UHD65 – figure that the cost difference of the different wheels (and wheel speeds) is minor, so pricing is set more by marketing and channels of distribution than costing a lot more to build.

The other difference is that the UHD60’s overall color wheel speed is slower. The UHD60's color wheel is 5 segments while the UHD65's have wheels are 6 segments, but the UHD65’s is a classic RGBRGB. The faster speed of the wheel means the UHD65 has the advantage over this UHD60 if you (as I am) are rainbow sensitive. If not, as is the case with most folks, then the color wheel speed is a non-factor, but I definitely do see the occasional rainbow flashes more often with the UHD60 than its big brother.

The UHD60’s wheel differentiates itself from the UHD65 by having color segments on the wheel to pass more light. The wheel itself is five segments, an interesting RGBCY – red, green, blue (the primary colors), C (cyan), and Y (yellow), two of the three secondary colors (missing is Magenta). While wheels do not need more than RGB, there are color performance advantages to adding others, but also a potential cost in brightness. The most egregious setup is to have a large clear slice on a color wheel, which is not the case here, per Optoma. That results in very low color lumen counts compared to white lumens. Long ago, we did a video on color lumens where we explain, for those who love the technology, how a clear slice adds white lumens, and costs color performance, complete with running the numbers. That’s a good trade-off many times, especially in projectors designed for brighter rooms.

The difference in the two wheels works out to a claimed 800 white lumens difference, but also a difference in color lumens (although we do not measure color lumens normally).

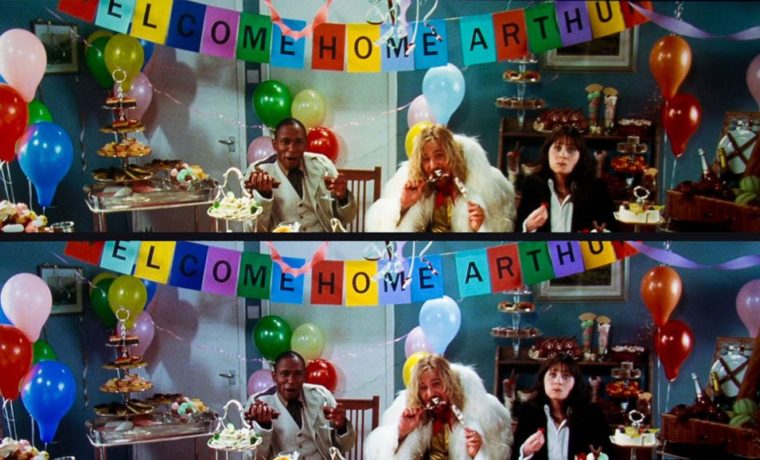

We are not talking huge differences, as you can see by this split screen image. (More such images in the picture quality pages.)

In these split screen photos, the upper image is the UHD65, while the lower half is the UHD60. I cropped out part of the middle and brought down the top image so you can see the same content on both, one on top of the other.